August 8, 2017

Chief Cameron S. McLay (Ret.)

Chief Cameron S. McLay (Ret.)

These are tough times for those of us in policing…

The crisis of confidence and legitimacy that characterizes post-Ferguson policing illustrates a vital lesson for local governments and their police. We, the police, must hold ourselves accountable for the outcomes of our policing services. We must measure our work and our outcomes based on a broader number of measures than simply measuring crime rates, and must continually reexamine our efforts in response to feedback and performance short-falls.

As with education and health care, policing would be well served by becoming more outcome-based. If the purpose for police interventions is to reduce crime, fear and disorder, to create safe communities suitable for normal civic life to occur, the question “Are we being successful in achieving these outcomes” must be part of the calculus. In other words, each police agency must operate as an open system, using feedback as a learning loop for constant performance improvement — becoming more responsive to to public needs and mindful of the impact of our efforts.

The foundational concepts of modern policing dates back to Sir Robert Peel in England in the 1820s. Under this paradigm, the police are simply an extension of the community — those citizens paid to perform the duties incumbent upon every citizen in a free democracy to contribute to the maintenance of safety and public order. Police success is dependent upon the cooperation of the public, and their power emanates from the consent of those served. Police are to be judged by the absence of crime, disorder and fear, rather than the measures of their enforcement work.

Policing’s desired outcomes are simply less crime, less fear and people having a greater sense their community is a safe and just place. We teach this to every recruit going through our academies. How many of us can rightly claim our communities feel our agency’s performance and systems reflect this value system?

Unfortunately, police agencies often do not measure their performance based upon community outcomes and public sentiment as a focal point. We, the police, have long believed as long as we perform our work well, as defined by standards we established, public opinion about our services is not vitally important.

Police-community relations, in this paradigm, is mostly about educating the public about what we do, and why we do it that way. We tell ourselves, “if they only understood us better, the public would finally understand and accept the outcomes of our policing efforts.”

To be competitive, private companies have long since learned the importance of data analysis to monitor and manage their organizational performance. Private companies do not survive unless they hold themselves accountable for performance outcomes. Their products and services must satisfy the demands of their consumers, must be high quality, and must be affordable if they are to compete.

Police and many government agencies have historically operated with the assumption their monopoly for service delivery makes customer satisfaction, and cost/benefit analysis, less important for their successes. Forgetting police performance requires public cooperation, we tend to believe we, the police, are the most well-informed judges of quality police services. The concept of controlling costs, especially social impact costs, tends to be alien to all but the most conscientious police executives.

The fact is, as with private sector agencies, the outcomes of our policing efforts matter. When police are successful, our contribution is nothing less than bringing peace and justice to those we serve. But when we fall short, we find communities held hostage to fear — distrustful of those employed to keep them safe. The stakes are indeed high.

With the development of CompStat in the mid-1990s, the NYPD pioneered the application of data analysis to measure and manage agency efforts to reduce crime and disorder. Today, CompStat-style performance management systems are widely viewed as a best practice in policing.

The use of data, hot-spot policing, “putting cops on the dots” of crime maps has arguably been highly successful in driving down reported crime, but it has had unintended consequences in some communities. When police target those communities where crime and violence is the highest — too often communities of poverty and color — the resultant enforcement efforts often created significant, albeit unintended consequences.

Fire departments go where the fires occur. Police agencies often find themselves in a “Catch-22” when they direct their enforcement efforts on those areas their crime data shows to be areas of highest concentration of crime and victimization. The reality in the U.S. is areas of poverty are often communities of color. Racial disparities in police contact and arrest are common when police, motivated to protect communities and fight crime, find themselves focusing their enforcement efforts on those few communities where crime concentration is the highest. Police are morally and legally obligated to provide safe communities for all, but when they do public trust and confidence can suffer greatly due to the racial disparities that typically follow.

There is a place in the middle. Police must work with the active engagement of community residents, to become partners in creating safe neighborhoods. Without the engagement of those living in the impacted areas, perceptions of predatory motivations for police actions can result, further diminishing trust between police and those receiving police service. At a time when crime is a near 20 year low point, studies have shown little if any increases in public trust, and dramatic differences in beliefs about police between white and non-white respondents.

How then to we continue to be effective in driving down crime, while addressing the unintended consequences of our policing efforts?

The current crisis of confidence facing policing has mobilized many to examine how to address this dilemma. George Kelling, the father of “Broken Windows Theory” of policing, has called for policing to be measured by on a broader set of performance metrics:

“Compstat is the most important administrative policing development of the past 100 years. Compstat appropriately focuses on crime, but I think the danger is that Compstat doesn’t always balance that focus with the other values that policing is supposed to pursue…. I want Compstat to measure and discuss things like complaints against officers, and whether police are reducing fear of crime in the community. The Compstat systems of the future must reflect all of the values the police should be pursuing.”

—Dr. George Kelling, Rutgers University

The challenge then becomes how to best enhance the effectiveness of police agencies in reducing crime and disorder, while also building public trust and confidence. How do we lower victimization rates, create safe public places and ensure police are meeting the quality of life needs of each of the communities they service, and also identify any unintended adverse impacts of police interventions in time for corrective action? How do we ensure police actions exact no unacceptable social costs?

Let’s learn from policing’s successes, like CompStat and the wide variety of highly positive community engagement and problem-oriented policing interventions, and from the private sector’s innovations for measuring customer impact. We need data; we need engagement, and we need to know how our services are impacting those we serve.

Private sector has long engaged in the use of data analytics to understand customer satisfaction and to better understand the market in which they operate. Companies often use data on enhancing productivity, improving product quality and streamlining inefficiencies. Just companies use market analysis and customer satisfaction as another vital barometer of performance. Each change in products or operations is tracked for its impact on customer satisfaction and impact on market needs.

In order to build trust and confidence — perceived legitimacy with the public — police must develop more complete performance metrics to measure and manage 21st Century policing. They must use data analytics to measure and manage organizational and individual member performance. They must hold themselves and their members accountable for the performance outcomes of their work, to include the impact of their actions on public perceptions of safety, justice and satisfaction with police service. Perhaps most important, elected officials must understand and embrace their responsibility to ensure their constituents receive the quality of police services they deserve.

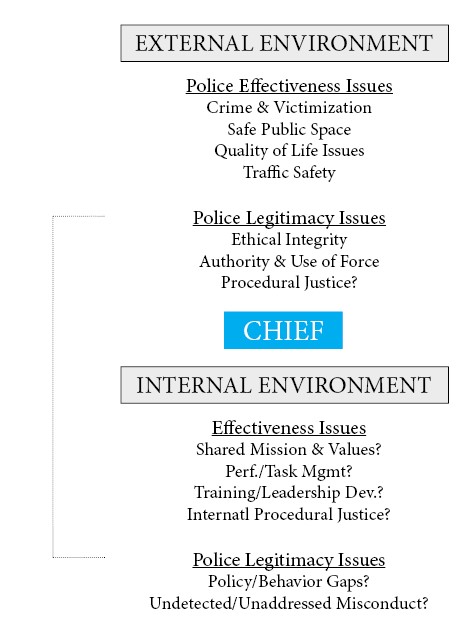

Performance management systems robust enough to meet the challenges of policing today would necessarily have the capacity for examining service impacts and outcomes with respect to the agencies’ external environment — the impact of those services on the communities, as well as capacity to monitor and measure the performance and behaviors of the individuals and groups in the agency — are they performing to the highest professional and ethical standards? The following graphic illustrates a police chief’s data needs.

Note the subjective nature of a great many of these measures. Certainly reported crime, calls for service, arrests, citations and other artifacts of police activities are objective measures, and are comparatively easy to count. However, whether the community feel safe in public spaces, the extent police are effective in addressing the quality of life, the extent to which police operate with integrity, and are judicious in their use of force and authority are subjective measures. These measure reflect how community members “feel” about the quality of life in their communities and the policing services they receive; they reflect social sentiment.

If police agencies are to become outcome-based, operating as “open systems,” they must have mechanisms for measuring social sentiment — the subjective experiences of those receiving police services, and must use this feedback to adjust service delivery when appropriate to ensure the desired outcomes, like reducing crime, a not occurring with unacceptable social costs like lost public trust.

Note also, the interdependent nature of these performance domains. Police effectiveness in reducing crime and victimization, creating safe public spaces, improving the quality of life, etc. is entirely dependent upon internal dynamics. The members must be fully engaged in the mission and values of the agency; be well trained to perform their roles; be properly managed and led, and use conduct themselves in ways to does not undermine public support and cooperation, or harm the reputation of the organization itself.

In the academic and research communities, forward thinking groups like the National Policing Institute, a D.C. based non-profit research group, have partnered with the Vera Institute for Justice to develop “CompStat 2.0” — developing performance metrics for all aspects of 21st Century Policing. At New York University’s Policing Project, researchers are working to develop methodologies to measure the “social costs” of policing, in order to permit cost-benefit analyses to be applied to police decision-making.

Historically, police have relied on community surveys to measure social sentiment, if they did so at all. Surveys are slow and expensive — insufficient to be able to provide meaningful data for measuring the impact of recent police interventions or community events. Using data mining, or advanced “big-data” analytics, the capacity exists today in the private sector to conduct in-depth sentiment analyses that serve as a feedback loop for executive decision-makers to understand market sentiment and to detect corporate risk. By accepting the necessity for such information as a vital component of performance management, these capacities can be incorporated into police performance management systems.

We in policing need to have the will to accept such feedback and the willingness to embrace partners in innovation. The NYPD, for example, has begun a pilot program for real-time sentiment analytics to be incorporated into their CompStat data. Police commanders will be expected to factor such sentiment public trust and satisfaction as they work to reduce crime and calls for service.

By combining performance management metrics designed by leading experts in policing, with advanced data-analytics to measure and monitor for emerging trends that create social harm if unaddressed, police decision-makers will be able to enhance their ability for forecast and respond to emerging crime and public order issues; enhance the effectiveness of their response to those problems; develop ways to measure the impacts, both intended and unintended, of police interventions, and create robust systems of accountability.

Building public trust and confidence – police legitimacy can be achieved when our services the communities we serve believe us to be effective and that our officers and agencies operate at the highest standards of professional conduct. Data analysis is the key to both. It takes data to identify emerging trends and direct police resources. It takes data to discern emerging employee problems or poor performance trends, and, for building trust, data transparency is an organization’s best vehicle for proving the quality and integrity of our systems.

In today’s perpetual whitewater of social/political/technological change, those objectives can best be achieved by agencies operating as “open systems,” constantly learning from and responding to feedback. Robust performance management systems, leveraging the capacities of data-analytics can provide us the capacities we need to meet the challenges of facing policing today, enabling the profession to earn a measure of public trust and confidence along the way.

Retired Chief Cameron S. McLay, formerly chief of police for the city of Pittsburgh (PA) Bureau of Police, is principle of TPL Public Safety Consulting and serves as senior adviser for PricewaterhouseCoopers Safe Cities Initiative — an initiative to enable police use of enhanced data analytics and monitoring of social risk and sentiment to improve their performance outcomes and to build public trust and confidence.

McLay has a master of science from Colorado State in organizational leadership, and a bachelor of arts in forensic studies from Indiana University. McLay served for more than 29 years with the city of Madison (WI) Police Department, where he retired with the rank of captain. He went on to teach leadership in police organizations for the IACP before serving as Pittsburgh’s chief.

Disclaimer: The points of view or opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Policing Institute.

Written by

Chief Cameron S. McLay (Ret.)

Strategic Priority Area(s)

Topic Area(s)

For general inquiries, or to submit an essay for consideration, please contact us at info@policefoundation.org.

Share

Strategic Priority Area(s)

Topic Area(s)

For general inquiries, please contact us at info@policefoundation.org

If you are interested in submitting an essay for inclusion in our OnPolicing blog, please contact Erica Richardson.

Share